Matrix Operations in Shaders

This post is about vector matrix operations in shaders, and how they are treated by today’s GPUs. This seems like a pretty mundane topic of discussion, but there are a few things which seemed interesting to bring up.

Matrix Storage

There are two canonical ways to represent a matrix(2-dimensional entity) in memory(which is 1-dimensional) - Row Major and Column Major. For a matrix

\[\begin{bmatrix} m_{11} & m_{12} & m_{13}\\ m_{21} & m_{22} & m_{23} \\ m_{31} & m_{32} & m_{33} \\ \end{bmatrix}\]Row Major stores the elements as \(m_{11},m_{12},m_{13},m_{21},m_{22},m_{23},m_{31},m_{32},m_{33}\), and Column Major stores the elements as \(m_{11},m_{21},m_{31},m_{12},m_{22},m_{32},m_{13},m_{23},m_{33}\).

Whether a matrix is stored in row-major or column-major form depends on the language1. C++ uses row-major, whereas HLSL uses column-major2 by default. As a result, if you have a matrix in C++ and pass the memory blob of the matrix to HLSL, the rows are read in as columns. The matrix is transposed!

This is why matrices are transposed on the C++ side before binding to HLSL because \((M^T)^T = M\).

Or alternatively you can use #pragma pack_matrix(row_major) in HLSL to make the storage match C++. (Thanks to @optimizedaway for pointing this out.)

Vector Transformation

Vectors can be represented in two different ways as well - they can either be represented as a \(n\) x \(1\) matrix such as \(\begin{bmatrix} v_1 & v_2 & v_3 & \cdots \end{bmatrix}\) or as a \(1\) x \(n\) matrix such as \(\begin{bmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \\ v_3 \\ \vdots \end{bmatrix}\). The first type is referred to as Row Vector and and latter one is a Column Vector. The two representations are transpose of each other.

For a matrix \(M\) and vector \(\vec{v}\), a row vector transformation is defined as \(\vec{v}M\). Conversely, a column vector transformation is defined as \(M\vec{v}\).

Also, note a vector matrix product can be represented as a dot product of the vector \(\vec{v}\) with a vector represented by each column of the matrix.

\[\vec{v}M = \vec{v} \left[ \begin{array}{c:c:c} m_{11} & m_{12} & m_{13}\\ m_{21} & m_{22} & m_{23} \\ m_{31} & m_{32} & m_{33} \\ \end{array} \right] = \begin{bmatrix} \vec{v}\cdot\vec{m_1} & \vec{v}\cdot\vec{m_2} & \vec{v}\cdot\vec{m_3} \end{bmatrix}\]Now consider, \(\vec{s} = \vec{v}M\). Then

\[\vec{s}^T = {(\vec{v}M)}^T = M^T \vec{v}^T\]Now, in a strictly mathematical sense, \(\vec{v}^T \neq \vec{v}\). However, HLSL does not distinguish between row and column vectors. A float4 can represent either one, and it is the context in which it is used, that determines whether it is treated as a row or column vector. Therefore, for the case of HLSL we can write

What this basically means, is that if we skip the matrix transpose on the C++ side (as discussed earlier) and we change the multiplication order in the shader, we get the same result!

This is a case of two wrongs make a right, and can be a source of confusion in the code base - so I don’t think anyone would recommend doing that. However, are there any unintentional side effects of doing this?

Vertex Shader Example

Consider a simple vertex shader that takes in a matrix as a structured buffer parameter.

StructuredBuffer<float4x4> Matrices;

float4 main (float4 pos : POSITION) : SV_Position

{

return mul (pos, Matrices[0]);

}

The corresponding DX bytecode looks like this

ld_structured_indexable(structured_buffer, stride=64)(mixed,mixed,mixed,mixed) r0.xyzw, l(0), l(0), t0.xyzw

dp4 o0.x, v0.xyzw, r0.xyzw

ld_structured_indexable(structured_buffer, stride=64)(mixed,mixed,mixed,mixed) r0.xyzw, l(0), l(16), t0.xyzw

dp4 o0.y, v0.xyzw, r0.xyzw

ld_structured_indexable(structured_buffer, stride=64)(mixed,mixed,mixed,mixed) r0.xyzw, l(0), l(32), t0.xyzw

dp4 o0.z, v0.xyzw, r0.xyzw

ld_structured_indexable(structured_buffer, stride=64)(mixed,mixed,mixed,mixed) r0.xyzw, l(0), l(48), t0.xyzw

dp4 o0.w, v0.xyzw, r0.xyzw

Pretty standard. There are 4 loads which fetch each column of the matrix into a register. The transform is, therefore, a simple dot product between the row vector and each column of the matrix (which in this case conveniently resides in the same register).

Now if we change the order of multiplication in the shader to mul(Matrices[0], pos), it generates the following asm.

ld_structured_indexable(structured_buffer, stride=64)(mixed,mixed,mixed,mixed) r0.xyzw, l(0), l(0), t0.xyzw

mov r1.x, r0.x

ld_structured_indexable(structured_buffer, stride=64)(mixed,mixed,mixed,mixed) r2.xyzw, l(0), l(16), t0.xzyw

mov r1.y, r2.x

ld_structured_indexable(structured_buffer, stride=64)(mixed,mixed,mixed,mixed) r3.xyzw, l(0), l(32), t0.xywz

mov r1.z, r3.x

ld_structured_indexable(structured_buffer, stride=64)(mixed,mixed,mixed,mixed) r4.xyzw, l(0), l(48), t0.xyzw

mov r1.w, r4.x

dp4 o0.x, r1.xyzw, v0.xyzw

mov r1.x, r0.y

mov r1.y, r2.z

mov r1.z, r3.y

mov r1.w, r4.y

dp4 o0.y, r1.xyzw, v0.xyzw

mov r2.x, r0.z

mov r3.x, r0.w

mov r3.y, r2.w

mov r2.z, r3.w

mov r2.w, r4.z

mov r3.w, r4.w

dp4 o0.w, r3.xyzw, v0.xyzw

dp4 o0.z, r2.xyzw, v0.xyzw

There is a lot more clutter - all those additional mov ops to retrieve the matrix rows so that we can compute the dot product seem like overkill. You can fix this by passing in individual matrix columns from C++, reading them in as float4 and reconstructing the matrix on the fly in the shader as discussed in this post3. But before that, let’s see what the effect of that will be.

Going Deeper

The above bytecode is only an intermediate representation - it is not what gets executed on the GPU. The graphics drivers perform the final compilation step to generate the ISA code.

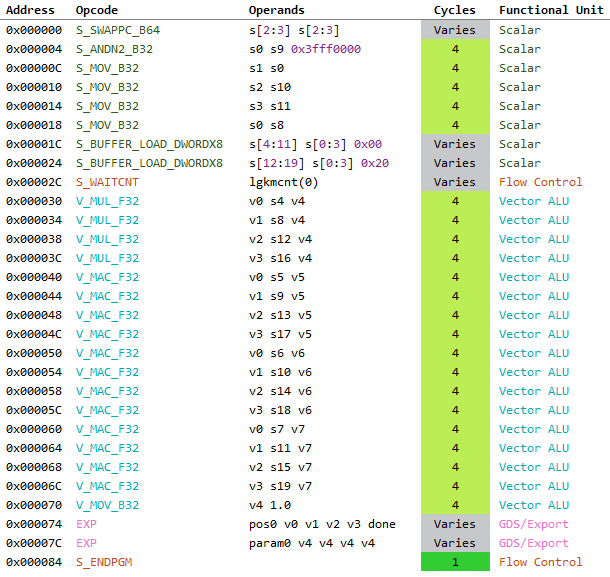

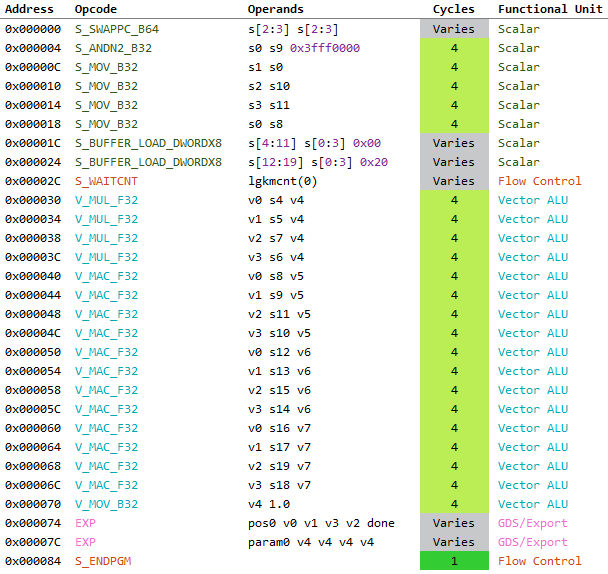

The following shows the ISA for the two cases side-by-side compiled for AMD Ellesmere (GCN 4th Gen).

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

They are identical! At least for the things we care about. Even the GPR usage is same at 18 SGPRs and 8 VGPRs.

…hmmm

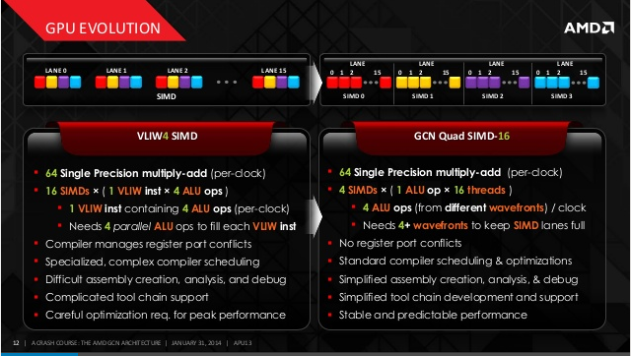

This actually makes sense when you consider that GCN architecture is “scalar”. In GCN4, unlike VLIW based architectures like Terascale5 previously, each VALU operates on a single float or integer at a time (although the process happens for 64 threads simultaneously).

(Thanks to @rygorous for the correction related to Terascale. Terascale was VLIW but scalar as well.. Not SIMD!)

“From the shader’s point of view each instruction operates on a single float or integer. That is what “scalar” means when discussing the architecture. However, the hardware will still run many instances of the shader in lockstep, basically as a very wide SIMD vector, 64 wide to be precise in the case of GCN, and that is what we refer to as vector instructions. So where the shader programmer sees a scalar float, the hardware sees a 64 float wide SIMD vector.” - Emil Persson (GDC ‘14)

Or in other words, GCN is SIMT as opposed to SIMD. The same is more or less true for Nvidia as well 6 7 8 9.

So, our fancy asm dp4 is gone and replaced with multiplications and additions (well, V_MAC_F32 to be specific). As such there is no noticeable improvements to be had in current gen hardware by optimizing matrix layouts to cleanup the DX asm above.

Conclusion

I did notice a 1-2% improvement on a test case from the cleanup, but that is within the margin of error and if anything has got to do with memory access patterns for the matrix elements. Although matrix layout organization may not bring any perf gains, sticking to one convention and being consistent can help avoid major headaches down the road, and keep things more portable.